These that follow are some books that I believe deserve a mention. Either pure literature, art or history, to read or just to browse through them, each one has some quality that makes it very special in the lot.

Simone Weil. Le pesanteur et la grâce.

In her very short life, Simone Weil evolved from socialism (in its original sense) towards Christianity. All that evolution was guided by a true concern for all those who needed help, and a real compromise to do help them. With a solid academic background, she wrote her reflections in diaries or letters, mostly published posthumously. Her writtings offer a pure crude vision of whom we must take care of and how, of what we can and cannot do from physical grievances to spiritual needs. Thus she considers strictly material proposals as well as deep religious feelings. She writes artfully like a scientist: exactness and economy, where every word matters. One should read every single sentence looking for apparent and hidden meanings. The collected thoughts gathered in the book I propose here are the best door to Weil’s ideas and message, and most likely will make the reader look for others. I suggest reading her harmonious crystalline french, with companion a good translation to one’s native language.

Ana María Matute. La puerta de la luna. Cuentos completos.

This book compiles all short stories by the author, from half a page long to 38, from poetry to drama, from legend and mistery to stark reality and social conscience. How singular each story is! The tone, the pitch, the style, the meaning, the depth… always different, arresting, fetching. Each complete, yet each belongs to a bigger scene, and one tracks it in another turning pages back more than often. The reader will experience surprise, pain, gloom, sorrow, anger, outrage, delight…, will reread to find anew. Among so many masterpieces, I mention Sino espada (1967) and La pared de los heliotropos (1968). And also No tocar, a story matching The mission of Jane (1902) by Edith Wharton.

Robertson Davies. The Deptford Trilogy:

Fifth business. The manticore. World of wonders.

The story catches the reader from the beginning: the people, the events, how they evolve along the years. So many surprises, so many unexpected twists, so many situations one cannot wait to see what happens next. And in the end, one is amazed the way everything has been told, so many pages that read so quick! Wonderful story, and wonderful literature too.

John Irving. The world according to Garp.

This is a strong story of a man, and the people he meets, loves or hates. A unique character, a unique story. Plenty of power and appeal, everything leading to definite purpose. There is fun and happiness, a lot, but also drama and disgrace. Sad things do happen, and very sad indeed, but in the end most of them fit well together. All in all, a book to be read on a whole.

Gonzalo Torrente Ballester. La saga/fuga de J.B.

Maybe the best novel by one of the best Spanish novelists. The reader feels the author mastering the language, the art of telling stories. In addition, and very important, what stories! Magnificent literature to tell a magnificent tale. Furthermore it has the magic of Galice, old and new. A book that remains in the memories of anyone who reads it.

Luis Mateo Díez. La fuente de la edad.

This book reads as a charm! The prose flows and the story traps the reader, with its mixture of magic and common life, on the edge of fantasy and reality. Yet, what a mistery. A rural quest of eternal life, including a good dose of sense of humour and wisdom. And the reader never feels the urgengy of skipping a single paragraph, as each single paragraph has its special beauty.

La Historia del Arte contada por Ernest H. Gombrich.

That’s of course a classic, and nobody should miss it. And then anybody will recommend others to read the book, and hopefully in the end everybody will have read the book. The best history of art ever written to be read, quite humbly described as «a story of art» by the author himself. Things plainly explained, which is only possible for an author who truly understands. A masterpiece.

The Times. Atlas of World History.

For those who love maps and history. A precious account of splendid graphics and images. A pleasure to view, and a perfect way to catch the big historical events and the evolution of cultures and civilizations.

The Times. The World: an illustrated history.

This direct, down to earth, sparkling book, is the best companion to the Times Atlas of World History. With lots of illustrations and a very visual presentation, to keep the reader’s attention always fresch.

John Steinbeck. Los hechos del rey Arturo.

Here there is the everlasting story of King Arthur and Camelot. The story everybody knows, in the words of a writer as powerful as John Steinbeck. Most likely the best single book to tell the Round Table feats. Anyway, who will not look for more? And we have Sir Thomas Mallory, but also Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant!

Ana María Matute. Olvidado Rey Gudú.

This is a book that stands apart and very high. A story comparable to any other epic saga. It mixes legend, history, magic and literature. It contains the truth of real life in ancient times, despite how fantastic the events go; there is a quality of contention, despite how big people behave. Outstanding, impressive.

Rebecca Goldstein. The mind-body problem.

This book has a special bias: it speaks of pure science, of mathematicians. Some will recognize the names, places and events that compose the background, and enjoy that a lot, but those who cannot catch such hidden references will anyway benefit from the soundness they give to the story. And the story goes on about the atypical way a researcher in Mathematics values merit. At the core of it, the desperate need of achieving some own outstanding original result, mixed with the constant fear of not being able to do it. On top, the book exposes the even worse fate of loosing inspiration, of losing the sparkle. Quite dramatically, sooner than later this is always the case for every mathematician, who must bear that lost of power, and a hard lost it is! Those who see mathematicians as somehow weird people dwelling in an ivory tower of little reality will be touched by this novel.

Geoff Dyer. But beautiful.

Jazz is the music one loves, jazzmen are the people that create it. You cannot love the art without being fascinated by the artists. This book is mostly about them, and the author expresses the stuff well: stories that go on smoothly to take the reader to the middle of all of it, which can be sometimes sad. There with the big names: Lester Young, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk…, and Duke Ellington all along the way. One can rather say that this book is jazz itself. A jewel.

Daniel Pennac. La tribu Malausséne:

La Felicidad de los ogros. El hada carabina. La pequeña vendedora de prosa. El señor Malausséne. Los frutos de la pasión.

Each of these five novels is a treasure built up from some crime whose most likely suspect is the (never guilty) main character, Benjamin Malausséne. The author creates a full universe around the Malausséne tribe Benjamin is trying to take care of. The reader is mercilessly struck by every twist of the plot(s) and every action of the characters. A wholly remarkable work.

James D. Watson. The double helix,

a personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA.

(Edited by Gunther S. Stent.)

This is a wonderful description of the good and bad feelings behind scientific discovery. The story has the plus of refering to an exceptional piece of research, ADN, and the author is one of the main characters involved. But it unfolds aspects very little known to those who do not know research from the inside; research is as human as everything else, and also involves meanness and deception. And all is told with merciless sincerity! This edition has the additional gift of a good bunch of reviews by highly qualified people (Nobel winners included), where no-one falls short of criticism, much to the delight of the reader. But then this plus has a surplus: the review of the reviews, in the same vein. The book is a must!

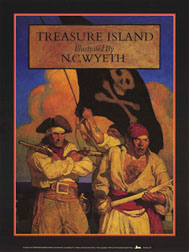

Robert Louis Stevenson. Treasure Island.

(Illustrated by N.C. Wyeth.)

Nothing can be added here to what everybody knows of this masterpiece of universal literature, but one can indeed stress the pleasure of reading this special reissue of the 1911 edition. Browsing through the powerful and fascinating plates while revisiting Stevenson’s novel surely gives an extra apreciation of story and characters.

Eric Hobsbawn The age of extremes,

a history of the world, 1914-1991.

This extraordinary book gives a full view of the world history from 1914 (First Word War) till 1991 (collapse of the Soviet Union), the period the author calls the short XXth century. There is a consistent effort to extract the essentials that shaped these years of upheaval. There is furthermore a successful attempt to orderly split the period into smaller parts, each distinguished by some main characteristic feature. And there is also a clear leftist bias, as the author confesses plainly: his is often a book of opinions, and the reader may very well not share them! In any case, this is a strongly advisable reading. Surely everybody will learn a lot.

Jan Swafford. The Vintage guide to classical music.

This is a book for many readings, always rewarding. Quite predictably, it will be good to read first the Introduction on pages xv-xxi, but all the same you can start on page 517, as the Afterword there serves well for introduction. Then you can read the preambles to the Renaissance, the Baroque, the Classical period, the romantic years… , all in a row a quick history of western music (and more). Less systematic, you can go straight to the biographies of your favourite composers, and along you can pick technical explanations from counterpoint to atonality. You will be captured by the author’s enthusiasm and expertise on the matter: is there anything better than someone who writes well on the topic he knows, and, up above, he loves? This book is compulsory reading!

William Sommerset Maugham. Diez grandes novelas y sus autores.

What about reading a book about books you’ve surely already read? This is serious, read this one: lots of common sense (hence little political correctedness) and true insight into ten universal masterpieces and their authors. To start with, a straight essay on why and how a novel must be read, and no mercy for scholarly reasons. Then many touching biographical scketches, sometimes crude, always honest, often against mainstream opinions, which lead the reader to a new view of those ten novels. That includes why they are not perfect: sure enough, more powerful and appealing than perfect,who bothers. After this reading, one is likely to retake classics, if ever let them down. A good enough reason to recommend this book.

Álvaro Mutis. Empresas y tribulaciones de Maqroll el Gaviero.

This thick volume contains the seven novels of adventures of Maqroll, a sailor compelled to suffer inland misfortunes. Good reasons to stick to these 774 pages: the beautiful language, the phylosophy that supports the main character through the episodes, the cast of men and women who scort Maqroll, the depiction of ambiences and places, the rareness of events… And that call, only too obvious, but maybe it is Conrad’s Heart of darkness. And also, isn’t this sailor a distillation of Corto Maltese? But not, Maqroll, is at ease nowhere, Corto anywhere; Maqroll has to leave, Corto wants to; Maqroll can’t stay, Corto need’t. From this book one retains the whole thing of course, but also many small pieces. And, in the end, one meets an Olrik! Is that a coincidence, or a toast to Blake & Mortimer?

Alain-Fournier. Le grand Meaulnes.

You must read this book. Don’t ask for any reasons, just read it and find them all. From scratch, this is a pleasure you’ll enjoy only once. Don’t spoil it. Read this book now, go. We can talk afterwards.

Pierre Mac Orlan. L’Ancre de Miséricorde.

It is said that this is the Treasure Island of french literature. And indeed there are ressemblances. But this book needs not them to ask for attention. It is adventure in the lost sense we all once enjoyed. Why not again? In addition, here there is an unusual ecstatic quality that pervades us. Everything goes around but we keep fixed at the same place all through the story. This is both enervating and sedative. Difficult to tell, very easy to feel. Try to.

Italo Calvino. Si una noche de invierno un viajero.

Italo Calvino. Si una noche de invierno un viajero.

This is a book to discuss further. One cannot classify it, neither needn’t. There is indeed a plot… First, this is a book, but then is about the character in that book, but then is about a reader of that book. Thus, this is a book about someone who reads one (soon many) books, but then about someone who writes those books, and someone else who fakes doing it, and someone else who reads those same books, and as it turns, the reader of the book is the reader in the book, reading the book and also reading the books in the book and learning about the others reading and writing those books, and looking at themselves doing it… and moreover all the readers and writers meet each other, and discover (or not?) what they are doing there… And in the end, there is no end and no story is fully told.. or is it? But surely any other reader of the book can tell a different story of and in the book.

Bernhard Schlink. El lector.

Bernhard Schlink. El lector.

This is a story. That’s something. A story very well told. That’s more than something. And a story that keeps the reader wondering what’s next, somehow surprised every now and then, at the right pace. And that would be enough for a story. But furthemore, along the reading the mere facts ask for a deeper understanding, for a better judgement on characters and events. At the end the reader will certainly concude this is not a light novel, as it hides profound and intense reflections underneath: emotion, compasion, pity. And unveiling them all is part of the artful simple (or not that simple?) writting of the author. And to mention a plus, one main guideline for the going is literature. This book really touches us in many ways.

Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio. Mientras no cambien los dioses nada habrá cambiado.

Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio. Mientras no cambien los dioses nada habrá cambiado.

More than half a century ago the author wrote the extraordinary Industrias y andanzas de Alfanhui. Ever since he’s been deploying his art in every astonishing way. The book here is again special. It is much of a thesis in the classical sense: a statement, the title, to defend. The 142 pages that follow contain its proof. This includes the full explanation of its meaning, and of course the argumentation, distilled to the essence. Afterwards, the reader can only accept the thesis: the title is actually self-explanatory. But only by the author’s powerful words… Learn it!

Herbert Rosendorfer. Cartas a la antigua China.

Herbert Rosendorfer. Cartas a la antigua China.

This is a parable. The idea is not new: pick a character who can take a (very large) distance to the modern western world and imagine how he will judge it. Here the character is a refinedly educated Chinaman from one thousand years ago. But this old trick pays well in this occasion: witty criticism, sensible conclusions, demolishing truths on today life-style. Where have harmony, soul and understanding gone? Quite pesimistic too, were it not for We-to-weng’s string quartets and french Moet Shang-dong.

Vikram Seth. Un buen partido.

Vikram Seth. Un buen partido.

This extraordinary novel achieves with impressive intensity the simplest main purpose of narrative: to rapture the reader into an accomplished different world, even alien to him, truer than life while abducted by the printed matter… And the feast of a panoply of so many different characters who love, hate, suffer, revolt, hide, disclose, laugh, cry and move the reader. That much to read… or rather, to look at and see, to listen to and hear, to smell, to feel. At the end, after 1350 pages it will take time to leave behind Lata, Amit, Haresh, Kabir, Malati, Kedarnath, Mrs Mehra, Pran, Saeeda Bai, Maan, Firoz, Imtiaz, Arun, Meenakshi, Kakoli, Veena, Bakshar, Mahesh Kapoor, the Baitar Nawab…, who are only a few. Unforgettable.

Sir Steven Runciman. La Caída de Constantinopla 1453.

Sir Steven Runciman. La Caída de Constantinopla 1453.

What is this? The history of the fall or a story of the fall? Actually, both, and all praise is deserved by the outcome. Gombrich’s way: You read history as a story. Thus you learn in the most friendly way: first the conditions that led to the siege of Constantinople, then the fight till the final capture of the capital and the consumption of the Byzantine Empire. And what a fight the author tells us! You can’t wait to read more, you can’t stop here, or there, and you go on only too quickly! Not to speak of quality: perfect writting, pure and elegant. For those renuent to history books: this is a breathtaking war tale! But behind of it, you are confident that the author is a master scholar of the topic.

Julian Barnes. Arthur & George.

Julian Barnes. Arthur & George.

Once again, what is this? A novel, a biography, social criticism? This book can be read in many moods. The story is a true one, and the characters are famous (worldwide one). The plot is intriguing (but the plot is not an invention, remember), and the author constructs it in the most orthodox detective story style (as his main character would). Imitation of life, or the other way around? A drama or a game? You can find yourself going backwards to confirm that something in your current page is soundly founded on certain casual comment many pages earlier. All in all, great narrative.

Walker Percy. Lost in the cosmos, the last self-help book.

It is dificult to understand the self, one-self. Furthermore, we are mature enough to know that no self-help book can give any help at all. But you’ll enjoy the various quizzes in this! Also, you’ll find a serious discussion on the nature of the self (your-self?). And if you are a scientist (true or fake), or an artist (true or fake), you may understand better your difficulties (true or fake) to adapt your self to your cosmos (or contrariwise). Of course you needn’t accept the theses of the author (true or fake).

Robertson Davies. The Cornish Trilogy:

The rebel angels. What’s bread in the bone. The lyre of Orpheus.

The very first book in this list of mine is the (maybe) best known of all Davies’ novels, written in the seventies. This one here (another trilogy) was written some 10 years later, but everything that was good remains good, and nothing else to be said. Only this hint: what can be better than a protagonist who wins as prize for his first school exploit two mythical art books: Burckhardt’s History of the Renaissance, and Vasari’s Lives of the Painters (and by the way, get these two, if you don’t have them). And there is much more in this vein…

Robertson Davies. The Salterton trylogy:

Tempest toast. Leaven of malice. A mixture of frailties.

This is another trylogy by Davies, in fact, the first one he wrote (in the fifties) and if you’ve already read the other two, there’s no need I insist further on this one: you’ll be eager for more. But if you haven’t read Davies yet, it’s high time, and since you’ll end up reading all you can, I will not make a point of the reading order you decide.

(I really have a thing for this writer.)

Rosa Sala Rose. El misterioso caso alemán,

Rosa Sala Rose. El misterioso caso alemán,

un intento de comprender Alemania a través de sus letras.

This fine essay treats a subject of general importance that concerns us all. The author develops her ideas in a smooth but fully rigorous and perfectly ordered discourse. She supports her arguments on precise data and properly chosen quotations, as one main stream is that literature may provide key reasons to understand history. Add to this interest and richness that the book joins elegant writting to scholar clarity. But also to praise is that the author expresses her ideas and drive her conclusions most plainly, with no cautious confusing nuances. And the final recommendation: if nothing else, go to a bookshop and read in a row the titles of the sections. I bet you’ll buy the book.

Rudyard Kipling. Relatos.

Rudyard Kipling. Relatos.

By the master of short narrative, mandatory!

Joseph Conrad. Entre tierra y mar.

Three off the mark stories, or tales, or nouvelles. The best qualities of Conrad are here. A smile of fortune, The secret sharer and Freya of the Seven Isles strike every key in the reader’s imaginary. I myself would go rather for the third, but this is only too subjective. All of them are perfectly rounded. No more, and no less.

Rohinton Mistry. Un perfecto equilibrio.

Muriel Barbery. L’élégance du hérisson.

Vraiment, j’ai aimé votre livre! Comment vous dites:

- Car l’Art, c’est la vie, mais sur un autre rythme.

- Moi, je supplie le sort de m’accorder la chance de voir au-delà de moi-même et de rencontrer quelqu’un.

- Le futur, ça sert a ça : à construire le présent avec de vrais projects de vivants.

- Malhereux les pauvres d’esprit qui ne connaissent ni la transe ni la beauté de la langue.

- Ainsi, sommes-nous civilisations si rongées par le vide que nous ne vivons que dans l’angoisse du manque? Ne juissons-nous de nos biens ou de nos sens que lorsque nous sommes assurés d’en jouir plus encore?

- Finalement, je me demande si le vrai mouvement du monde, ce n’est pas le chant.

- Quelle congruence entre un Claesz, un Raphaël, un Rubens et un Hopper? L’oeil y trouve sans avoir à la chercher une forme qui déclenche la sensation de l’adéquation, parce qu’elle aparaît à chacun comme l’essence même du Beau, sans variations ni réserve, sans contexte ni effort.

- Car l’Art, c’est l’émotion sans le désir.

- C’est peut-être ça, être vivant : traquer des instants qui meurent.

- Car, pour vous, je traquerai désormais le toujours dans le jamais.

And of course, the story is interesting, this is not just looking for smart sayings… Fun sometimes, irony, drama, and a strong, even tough, final touch that is the most moving thing I’ve read in many years.

Tony Judt. Ill fares the land.

Thanks, Mr. Judt. Thanks for the words, words, words:

- Something is profoundly wrong with the way we live today. For thirty years we have made virtue out of the pursuit of material self-interest: indeed, this very pursuit now constitutes whatever remains of our sense of collective purpose.

- The greatest extremes of private privilege and public indifference have resurfaced in the US and the UK: epicenters of enthusiasm for deregulated market capitalism. […] none has matched Britain and the United States in their unwavering thirty-year commitment to the unraveling of decades of social legislation and economic oversight.

- When imposing welfare cuts on the poor, …[legislators] have taken a singular pride in the ‘hard choices’ they had to make. […] These days, we take pride in being tough enough to inflict pain on others. If an older usage were still in force, whereby being tough consisted in enduring pain rather than imposing it to others, we should perhaps think twice before so callously valuing efficiency over compasion.

- The victory of conservatism […] took an intelectual revolution […] best summed up in Margaret Tatcher’s notorious bon mot: «there is no such thing as society, there are only individuals and families». […] This reduction of ‘society’ to a thin membrane of interactions between private individuals is presented today as the ambition of libertarians and free marketeers. But we should never forget that it was first and above all the dream of Jacobins, Bolsheviks and Nazis: if there is nothing that binds us together as a community or society, then we are utterly dependent upon the state.

- However, poverty –whether measured by infant mortality, life-expectancy, access to medicine and regular employment or simple inability to purchase basic necessities– has increased steadily since the 1970s in the US, the UK and every country that has modelled its economy upon their example. The pathologies of inequality and poverty –crime, alcoholism, violence and mental illness– have all multiplied commensurately. […] The social question is back on the agenda.

- The materialistic and selfish quality of contemporary life is not inherent in the human condition.

- Much of what appears ‘natural’ today dates from the 1980s: the obsession with wealth creation, the cult of privatization and the private sector, the growing disparities of rich and poor. And above all, the rhetoric which accompanies these: uncritical admiration for unfettered markets, disdain for the public sector, the delusion of endless growth.

- We cannot go on living like this.

- We have been swept up into a new master narrative of «integrated global capitalism», economic growth and indefinite productivity gains. Like earlier narratives of endless improvement, the story of globalization combines an evaluative mantra («growth is good») with the presumption of inevitability: globalization is with us to stay, a natural process rather than a human choice. The ineluctable dynamic of global economic competition and integration has become the illusion of the age.

- Having reduced the scale of public ownership and intervention over the course of the past thirty years, we now find ourselves embracing de facto state action on a scale last seen in Depression. The reaction against unrestrained financial markets –and the grotesquely disproportionate gains of a few contrasted with the losses of so many– has obliged the state to step in everywhere.

- And then came the ’80s: the first of two lost decades, during which fantasies of prosperity and limitless personal advancement displaced all talk of political liberation, social justice or colective action. In the English-speaking world, the selfish amoralism of Tatcher and Reagan –«Enrichissez-vous», in the words of the 19th century French statesman Guizot– gave way to the vacant phrase-making of baby-boom politicians. Under Clinton and Blair, the Atlantic world stagnated smugly. Until the late ’80s, it was quite uncommon to encounter promising students who expressed any interest in attending bussiness school. Indeed, bussiness schools themselves were largely unknown outside of North America. Today, the aspiration -and the institution- are commonplace.

We could keep quoting, quoting, quoting…